Introduction

This is the official book of the radare project.

This is a collaborative and community-driven project, if you want to improve the status of the documentation check out the contributing chapter and submit pull requests to the repository

- GitHub

- ePUB

- Online Html - built with mdbook

- Gemini Capsule - md2gmi

The minimum version of radare2 required to follow this book is r2-5.8.x, but it is recommended to always use the last release or build it from git.

Book Editions

This book was written with Halibut in 2009 by pancake focusing on radare. The initial implementation of the tooling, unfortunately the code evolved faster than the documentation did, and the book became obsolete, for historical reasons this version can be found in this webpage:

During 2014, Maijin reorganized and updated the contents, other contributors over the Internet also helped to get new stuff in and after some reviews the book was now readily available for the first time in PDF, ePUB and Hardcover printed versions.

Unfornately, the documentation part of the project got stuck again; and 10 years later, in 2024, pancake worked back updating and polish its contents. Looking towards the 3rd edition that may be ready by the end of the same year.

History

In 2006, Sergi Àlvarez (aka pancake) while working as a forensic analyst he decided to write a small tool to recover some deleted files from an HFS+ disk by accident. As long as using the privative software from work it was a good toy project, following the concept of a block-based hexadecimal editor interface with a very simple repl to enter commands to search for byte patterns and dump the results to disk. And have the following characteristics:

- be extremely portable (unix friendly, command line, c, small)

- open disk devices, this is using 64bit offsets

- search for a string or hexpair

- review and dump the results to disk

After three years of intense development (in 2009) the project was too bloated to keep it as a monolitic tool and pancake decided to redesign the tool into a more pluggable and modular form. This way it was possible to create scripts, bindings and write plugins to add support for more architectures, debugging targets or improve the analysis capabilities by keeping the core intact.

Since then, the project has evolved to provide a complete framework for analyzing binaries, while making use of basic UNIX concepts. Those concepts include the famous "everything is a file", "small programs that interact using stdin/stdout", and "keep it simple" paradigms.

The need for scripting showed the fragility of the initial design: a monolithic tool made the API hard to use, and so a deep refactoring was needed. In 2009 radare2 (r2) was born as a fork of radare1. The refactor added flexibility and dynamic features. This enabled much better integration, paving the way to use r2 from different programming languages. Later on, the r2pipe API allowed access to radare2 via pipes from any language, and the r2papi provided an idiomatic and high level interface to use r2 through r2pipe from a large list of programming languages.

What started as a one-man project, with some eventual contributions, gradually evolved into a big community-based project around 2014. The number of users was growing fast, changing roles and contribution rules to ease the maintenance as much as possible.

It's important to instruct users to report their issues, as well as help developers willing to contribute to understand the codebase. The whole development is managed in radare2's GitHub and discussed in the Telegram and Discord channels.

There are several side projects that provide, among other things, a graphical user interface (Iaito), a decompiler (r2dec, r2ghidra), Frida integration (r2frida), Yara (r2yara), Unicorn, Keystone, and many other projects indexed in the r2pm, the radare2 package manager.

Since 2016, the community gathers once a year in r2con, a congress around radare2 that takes place in Barcelona.

Toolchain

The Radare2 project provides a collection of command-line tools, APIs and scripting capabilities that focus on several aspects of reverse engineering.

This chapter will give you a quick understanding of them, but you can check the dedicated sections for each tool at the end of this book.

radare2

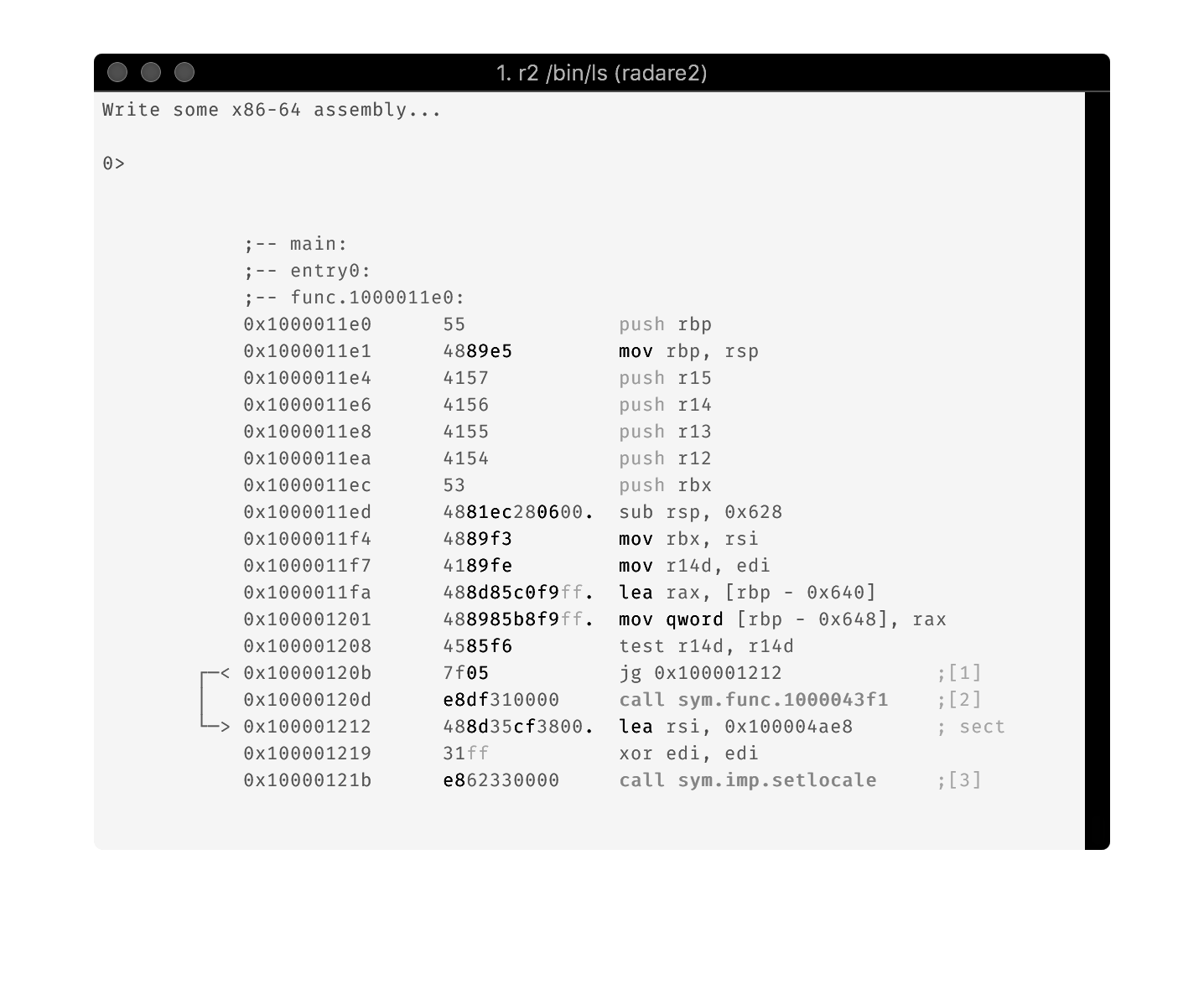

When you run the radare2 command, you're presented with an interactive shell that gives you access to all the functionalities of the radare2 framework by running mnemonic commands or scripts.

At its core, radare2 lets you open various types of files and data sources, treating them all as if they were simple binary files. This includes executables, disk images, memory dumps, and even live processes or network connections.

Once you've opened a file, radare2 provides a wide array of commands for exploration and analysis. You can navigate through the file's contents, view disassembled code, examine data structures, and even modify the binary on the fly.

Some key features accessible through the radare2 command include:

- Hex editing capabilities

- Advanced code analysis and disassembly

- Debugging functionality

- Binary patching

- Data visualization tools

- Scripting support for automation and extending functionality

The radare2 command serves as the primary interface to these features, offering a flexible and powerful environment for reverse engineering, malware analysis, exploit development, and general binary exploration.

rax2

A minimalistic mathematical expression evaluator for the shell that is useful for making base conversions between floating point values, hexadecimal representations, hexpair strings to ASCII, octal to integer, and more. It also supports endianness settings and can be used as an interactive shell if no arguments are given.

Examples

$ rax2 1337

0x539

$ rax2 0x400000

4194304

$ rax2 -b 01111001

y

$ rax2 -S radare2

72616461726532

$ rax2 -s 617765736f6d65

awesome

rabin2

Another important tool distributed with radare2, rabin2 is designed to analyze binary files and extract various types of information from them. It supports a wide range of file formats (depending on which plugins are loaded or compiled in), the most famous ones are:

- ELF (Executable and Linkable Format)

- PE (Portable Executable)

- Mach-O (Mach Object)

- Java CLASS files

Key features and uses of rabin2 include:

- Extracting metadata: File type, architecture, OS, subsystem, etc.

- Listing symbols: Both imported and exported symbols.

- Displaying section information: Names, sizes, permissions, etc.

- Showing library dependencies.

- Extracting strings from the binary.

- Identifying entry points and constructor/destructors.

- Listing header structures and information.

rabin2 can be used standalone from the command line or integrated within other radare2 tools. It's particularly useful for quick analysis of binaries without the need to fully load them into a debugger or disassembler. The information provided by rabin2 is often used by other parts of the radare2 framework to enhance analysis and provide context during reverse engineering tasks.

rasm2

The command-line assembler and disassembler. It supports a wide range of architectures and can be used independently of the main radare2 tool. Key features include:

- Multi-architecture support: Can handle numerous architectures including x86, x86-64, ARM, MIPS, PowerPC, SPARC, and many others.

- Bi-directional operation: Functions as both an assembler (converting human-readable assembly code to machine code) and a disassembler (converting machine code back to assembly).

- Flexible input/output: Accepts input as hexadecimal strings, raw binary files, or text files containing assembly code.

- Shellcode generation: Useful for security research and exploit development.

- Inline assembly: Allows for quick assembly of individual instructions or small code snippets.

- Syntax highlighting: Provides colored output for better readability when disassembling.

- Plugins: Supports architecture-specific plugins for extended functionality.

For example assembling and disassembling a nop for java:

$ rasm2 -a java 'nop'

00

$ rasm2 -a x86 -d '90'

nop

$ rasm2 -a x86 -b 32 'mov eax, 33'

b821000000

$ echo 'push eax;nop;nop' | rasm2 -f -

509090

rahash2

Versatile command-line hashing tool that is part of the radare2 framework. It's designed to compute and verify cryptographic hashes and checksums for files, strings, or even large data streams like hard disks or network traffic.

- Supports a wide range of hash algorithms

- MD4, MD5, SHA1, SHA256, SHA384, SHA512, CRC16, CRC32, and more.

- Input data from files, stdin, or command-line strings.

- Block-based hashing

- Incremental hashing for large files

- Hash verification

- Various output formats, including raw bytes, hexadecimal strings, or radare2 commands.

- Basic encryption capabilities

Here are few usage examples:

$ rahash2 file

file: 0x00000000-0x00000007 sha256: 887cfbd0d44aaff69f7bdbedebd282ec96191cce9d7fa7336298a18efc3c7a5a

Algorithms can be selected by specifying them separated with the -a flag.

$ rahash2 -a md5 file

file: 0x00000000-0x00000007 md5: d1833805515fc34b46c2b9de553f599d

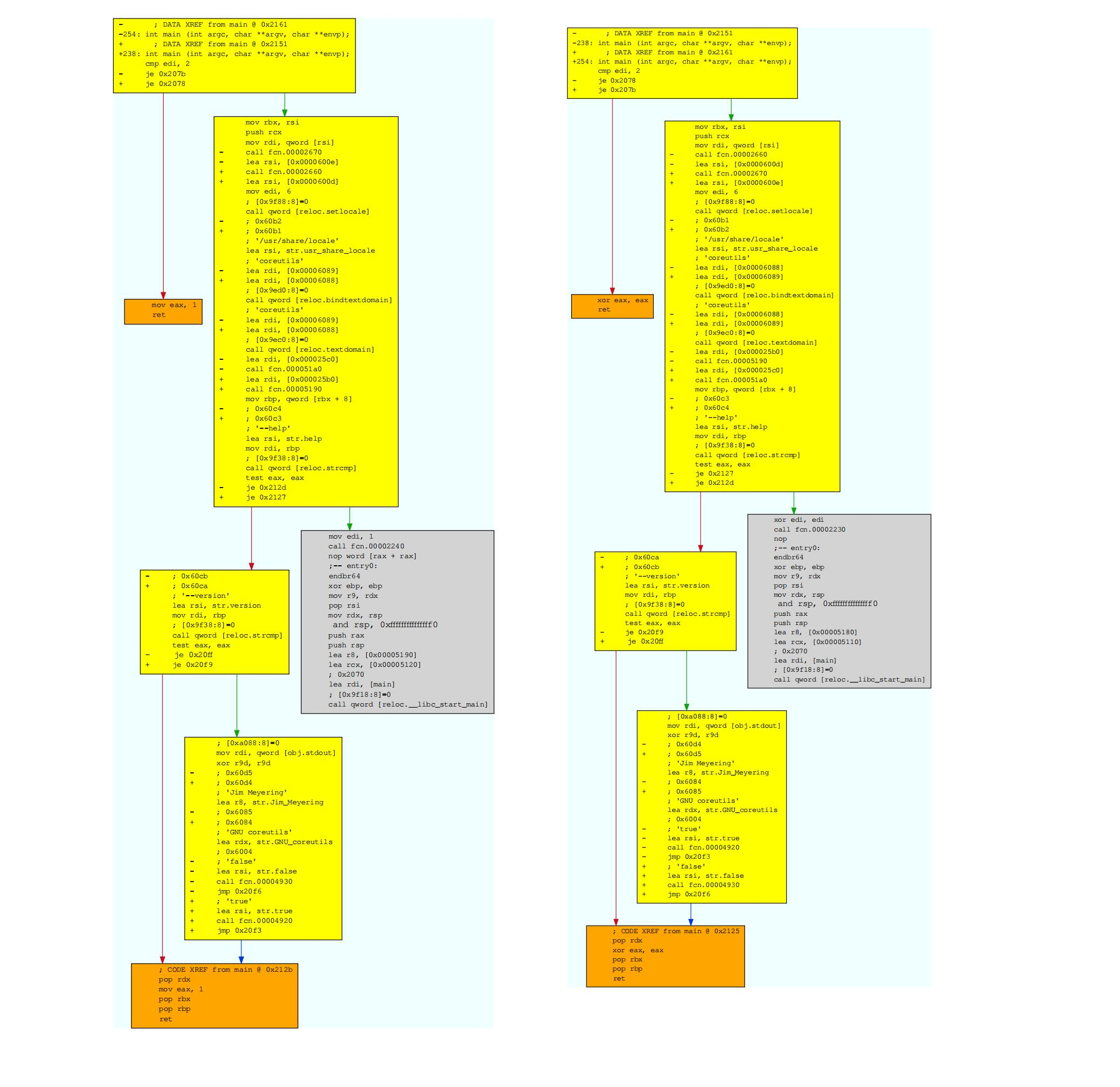

radiff2

The commandline Binary Diffing utility of the radare2 reverse engineering framework. It is designed to compare and analyze differences between binary files or sections of binary data.

Key features and capabilities of radiff2 include:

- Compare byte-per-byte changes between two files

- Delta diffing on files with different sizes, finding common sections

- Code Analysis diffing, finding functions in common

- Binary header comparing libraries, exports, etc

- Visualization options: graphs, ascii art, plain text, json

- Integration with radare2: Using the

ccommand or running it with the-rflag. - Patch generation, writing r2 scripts that patch one file to update it like the other.

radiff2 is particularly useful for cases where you need to identify and understand changes between different versions of binary files or compare potentially malicious files with known good versions.

rafind2

rafind2 is a command-line utility designed to search for byte patterns, strings, or hexadecimal values within binary files or any other type of file.

This tool implements the most common subcommands of the radare2's / (search) operation.

- Search for patterns, strings, binary data and regular expression

- Run across multiple files

- Output formats, showing offsets, json and even r2 commands

ragg2

Ragg2 is a versatile tool primarily serving as a shellcode compiler.

The tool is written on top of the r_egg library which can construct exploit payloads from the commandline, adding paddings, nops, sequences of bytes, compile small relocatable programs and even apply transformations to avoid some specific characters.

The ragg2-cc tool can compile C programs into raw linear instructions that are relocatable and are useful for injecting them in target processes or use them in exploits.

This feature is conceptually based on shellforge4, but only linux/osx x86-32/64 platforms are supported.

It can also compile a specific low level domain specific language and generate tiny binaries without the need of any system compiler or toolchain as exemplified below:

$ cat hi.r

/* hello world in r_egg */

write@syscall(4); //x64 write@syscall(1);

exit@syscall(1); //x64 exit@syscall(60);

main@global(128) {

.var0 = "hi!\n";

write(1,.var0, 4);

exit(0);

}

$ ragg2 -O -F hi.r

$ ./hi

hi!

$ cat hi.c

main@global(0,6) {

write(1, "Hello0", 6);

exit(0);

}

$ ragg2 hi.c

$ ./hi.c.bin

Hello

rarun2

A launcher for running programs within different environments, with different arguments, permissions, directories, and overridden default file descriptors.

User Interfaces

Radare2 has seen many different user interfaces being developed over the years.

Maintaining a GUI is far from the scope of developing the core machinery of a reverse engineering toolkit; It is preferred to have a separate project and community, allowing both projects to collaborate and improve alongside each other. This allows individual developers to focus entirely on implementing a CLI or GUI feature instead of trying to juggle both graphical implementation and the low-level logic of the core CLI.

In the past, there have been at least 5 different native user interfaces (ragui, r2gui, gradare, r2net, bokken) but none of them got enough maintenance power to take off and they all died.

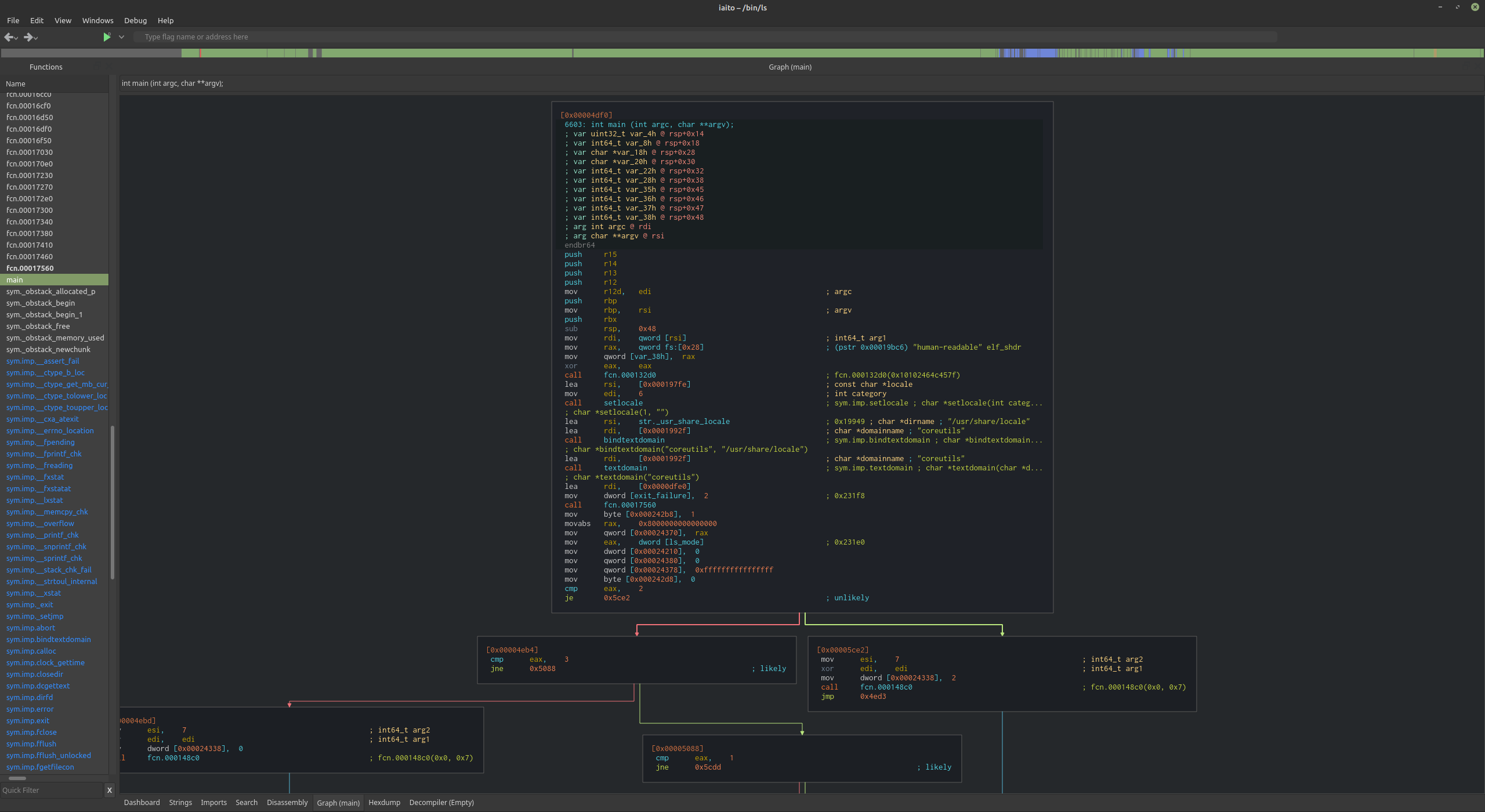

Iaito

The current main radare2 GUI is Iaito. It is written in C++ using Qt and was originally authored by Hugo Teso.

- Download: https://github.com/radareorg/iaito

WebUI

In addition, r2 includes an embedded webserver with a basic HTML/JS interface. Add -c=H to your command-line flags to automatically start the webserver and open it in your browser.

$ r2 -c=H /bin/ls

r2con

Starting in 2016 we organized the first public and international congress about radare.

Highlighting all aspects of radare2, this congress brings the oportunity to everyone to learn more about manual and automated reverse engineering, static and dynamic analysis, fuzzing, forensics, exploiting, unpacking, malware, ... this congress allows everyone to understand how to use r2 and how to extend it for your own purposes, it will also serve as an excuse for all developers to meet and discuss design and implementation tips for the future of the project.

The congress was started as a 2 days filled with trainings and presentations.

Other rules and aspects that make r2con a special conference:

- Chill ambient with beers and sunny weather

- All presentations are recorded and published (some trainings too)

- Located in Barcelona, organized the 2nd week of September

- Small event, started with 50 attendeeds, reached it's top with 300

- r2wars and crackme competitions

- Vegan meals

- Chiptune party

Contribute!

If you want to contribute to the Radare2 book, you can do it at the Github repository.

Suggested contributions include:

- Crackme writeups

- CTF writeups

- Explain how to use Radare2

- Documentation to help developers

- Conference presentations/workshops using Radare2

- Missing content from the Radare1 book updated to Radare2

Please get permission to port any content you do not own/did not create before you put it in the Radare2 book.

See https://github.com/radareorg/radare2/blob/master/DEVELOPERS.md for general help on contributing to radare2.

Installation

Radare2 is available for a wide range of target operating systems and architectures, making it a versatile tool for reverse engineering tasks.

Whether you are using Windows, Linux, macOS, or even mobile or embedded operating systems, radare2 can be installed and utilized effectively. This chapter provides a comprehensive guide on how to get radare2 up and running on your system, covering various methods from downloading and installing binary distributions to compiling the software from source code. This flexibility ensures that users can tailor the installation process to their specific needs and system configurations.

To install radare2, users can choose from several options. One straightforward method is to download precompiled binary distributions, which are available for many platforms and can be installed quickly with minimal setup.

But usually the recommended way to install is by compiling it from the git repository, the upstream branch is always stable and ready to use for everyone.

The chapter also delves into specific configuration options and post-installation setup to optimize radare2 for different use cases, ensuring that you have a fully functional and efficient reverse engineering environment which is key to follow up with the rest of contents in the book.

Downloading

You can get radare from the GitHub repository: https://github.com/radareorg/radare2

Binary packages are available for a number of operating systems (Ubuntu, Maemo, Gentoo, Windows, iPhone, and so on). But you are highly encouraged to get the source and compile it yourself to better understand the dependencies, to make examples more accessible and, of course, to have the most recent version.

Downloadable versions of the latest releases of Radare2 are available in https://github.com/radareorg/radare2/releases itself.

For distributions we aim to recommend the use of release source tarballs to build the program. But users may probably want to use the last code from git that's why we always mention "use r2 from git", because we don't aim to fix bugs in releases, always test your bug or problems in the last development branch master.

The radare development repository is often more stable than the 'stable' releases. To obtain the latest version:

$ git clone https://github.com/radareorg/radare2.git

This will probably take a while, so take a coffee break and continue reading this book.

To update your local copy of the repository, use git pull anywhere in the radare2 source code tree:

$ git pull

The most common way to get r2 updated and installed system wide is by using, but we may learn more about building

$ sys/install.sh

r2env

r2env is a lightweight tool version managers: either clone the repo and add its bin to your PATH and enable shell integration, or install via pip. The simplest option:

pip install r2env

This makes the r2env command available and sets up shims for r2 / radare2 so the active version is used automatically.

Replace <version-or-ref> with a tag, branch, or other reference you want to install.

r2env install <version-or-ref>

To remove a build later, use r2env uninstall (see the repo README for the exact syntax and any extra flags). If anything behaves unexpectedly, consult the r2env GitHub README for up-to-date flags, usage details, and platform-specific dependencies.

Helper Scripts

Take a look at the scripts in sys/, they are used to automate stuff related to syncing, building and installing r2 and its bindings.

The most important one is sys/install.sh. It will pull, clean, build and symstall r2 system wide.

Symstalling is the process of installing all the programs, libraries, documentation and data files using symlinks instead of copying the files.

By default it will be installed in /usr/local, but you can specify a different prefix using the argument --prefix.

This is useful for developers, because it permits them to just run 'make' and try changes without having to run make install again.

Building From Source

One of radare2's core development principles is portability; consequently, it can be compiled on many systems and architectures. To achieve this and maximize flexibility, we maintain two build systems: GNU Make (classic autotools style ./configure + make) and Meson (modern ninja-based builds).

Most contributors work on GNU/Linux with GCC or macOS with Clang, so those platforms are the most thoroughly tested and best supported. However, builds are also possible with TinyCC, Emscripten, Microsoft Visual Studio, Sun Studio, etc.

Some features can be disabled at compile time to tailor the binary for your environment:

- Pick which plugins are built (static vs shared)

- Choose system or bundled third-party libraries (capstone, openssl, zlib, etc.)

- Disable the native debugger

- Disable fork/exec support

- Disable threading support

The debugger can be disabled at configure time — useful for WebAssembly builds, sandboxed environments, or ports to platforms where the debugger is not supported. Use the --disable-debugger configure flag (or set -Ddebugger=false with meson) to disable it.

Currently, the debugger layer is available on many platforms (Windows, Linux, macOS, BSDs, etc.). Some I/O plugins are OS-specific and may require third-party tools such as GDB, WinDBG, or Wine.

Build systems overview

- GNU Make (./configure + make): traditional, flexible, well suited for Unix-like systems and advanced customization via environment variables.

- Meson + Ninja: faster incremental builds, better Windows support, declarative options. We expose most important knobs as meson options (see below).

Choose the system you prefer; both can be used to produce equivalent results.

Selecting plugins: ./configure-plugins (Make-based workflow)

radare2 ships with a small helper script named configure-plugins (found in the repository root). Its purpose is to generate plugins.cfg and the generated build headers/make fragments that control which plugins are built as static (compiled into the libraries) or shared (built as separate .so/.dylib files).

Key points:

- Default plugin list is taken from

dist/plugins-cfg/plugins.def.cfg. Whenplugins.cfgis missing,configure-pluginscopies the default file there. plugins.cfgcontains two shell variables:STATICandSHARED, which list plugin names in the formlib.plugin(for exampleio.debug,asm.x86)../configure-pluginsreadsplugins.cfgand generates:libr/config.h(macros describing which plugins are static)libr/asm/d/config.inc(gperf registrations for static asm plugins)libr/config.mk(Makefile fragments used by the build)

Usage and useful flags (from the script help):

./configure-plugins --shared name1 name2— mark the named plugins as shared (remove from STATIC and add to SHARED)../configure-plugins --static name1 name2— mark the named plugins as static (compiled into the relevant library)../configure-plugins --list— print the current static / shared lists../configure-plugins --rm-static <dir>— when provided a directory (e.g. an installation lib dir), remove shared plugin files that correspond to plugins marked as static (helper when switching a build to static plugins to avoid stale shared objects)../configure-plugins --without-gpl— useplugins.nogpl.cfgdefaults instead of the distributed one (useful to avoid GPL-only plugins)../configure-plugins -n— do nothing (don't generate files, useful to inspect what would happen).

Notes:

- After changing plugins with

configure-plugins, re-run./configureand rebuild (or re-run the Make build) so the generated headers and make fragments are picked up. - For Meson builds, plugin selection works differently (see the Meson options section). Meson has an option

-Dplugins='comma,separated,list'to build only a specific set of plugins.

If you want to customize further or need help choosing specific plugin names, check dist/plugins-cfg/plugins.def.cfg for the canonical default list, and src/plugins documentation (see src/plugins/dev.md) for guidance on plugin naming and structure.

The most relevant ./configure options (Make)

When using ./configure there are many options; these are the most commonly useful ones and how to use them.

-

Installation directories

--prefix=/path— set installation prefix (default/usr/local).--exec-prefix=EPREFIX— install arch-dependent files in EPREFIX.

-

Tuning the install paths

--bindir,--libdir,--datadir,--sysconfdir,--mandir, etc. — set specific target directories.

-

Cross-build settings

--host=HOSTand--build=BUILD— useful when cross-compiling.

-

Feature toggles (picks the most important ones)

--disable-debugger— build without native debugger support.--disable-threads— build without threading APIs.--disable-loadlibs— disable runtime loading of plugin libraries (forces static behaviour in some cases).--without-qjs— build without QuickJS.--without-dylink— disable dynamic loading of plugins.--without-fork— disable fork support.--without-ptrace-wrap— do not build ptrace-wrap support (used by some debugger backends).--without-gpl— avoid building GPL-only components.

-

Third-party libraries and system vs bundled

--with-capstone4,--with-capstone5,--with-capstone-next— choose which bundled capstone branch to build.--with-syscapstone/--without-syscapstone— force use (or avoid) system capstone.--with-syslz4,--with-syszip,--with-sysxxhash— force use of system libraries when available.--with-ssl/--with-ssl-crypto— enable SSL support if available.--with-libuv— prefer libuv when available.

-

Misc

--with-rpath— set rpath handling in built binaries.--with-new-abi— enable the new/experimental ABI changes.--with-compiler=...or setCC=environment variable to choose compiler.

Environment variables you will commonly set when invoking configure or make:

CC— C compiler (e.g.,CC=clang).CFLAGS— extra compiler flags (e.g.,CFLAGS='-O2 -g').LDFLAGS— linker flags (LDFLAGS='-L/opt/local/lib').CPPFLAGS— preprocessor flags (CPPFLAGS='-I/opt/local/include').

Examples (Make):

-

Build for local prefix and disable debugger:

./configure --prefix=$HOME/.local --disable-debugger make make install

-

Cross-compile example (simple):

./configure --host=arm-linux-gnueabihf --prefix=/usr make

After running ./configure (and/or configure-plugins) build with make or gmake depending on your platform.

Meson: options and how to use them

The Meson build exposes many options (see meson_options.txt). Meson options are passed via -Dname=value when configuring the build directory. Some common options and their meanings:

-

General build options

-Dlocal=true|false— prepare a local/side-by-side installation (sets rpath if needed).-Dstatic_runtime=true— link all libraries statically into the binary.-Dblob=true— build a single dispatching binary (calls different handlers depending on argv[0]).-Dwant_threads=true|false— enable threading support.-Ddebugstuff=true|false— enable handling of debug hooks and logs.-Dchecks_level=<int>— control assert levels (0..3).

-

Plugin selection

-Dplugins='comma,separated,list'— explicitly build only the named plugins (plugin names withoutp/prefix; uselib.pluginformat, e.g.io.debug,asm.x86).-Duse_dylink=true|false— enable (default true) building of shared plugin libraries.

-

Capstone / third-party selection

-Dwant_capstone=true|false— build capstone support.-Duse_sys_capstone=true|false— use system capstone instead of bundled.-Duse_capstone_version=v4|v5|next— select which capstone branch to use.-Duse_sys_magic=true|false,-Duse_sys_zlib=true|false,-Duse_sys_lz4=true|false,-Duse_sys_xxhash=true|false— prefer system libraries.

-

Debugger / runtime

-Ddebugger=true|false— build with debugger support.-Dwant_qjs=true|false— enable QuickJS runtime.-Dwant_ptrace_wrap=true|false— build ptrace wrapper support.

-

Tests and extras

-Denable_tests=true|false— build unit tests (test/unit).-Denable_libfuzzer=true|false— build libFuzzer targets.-Denable_r2r=true|false— build the r2r regression executable.

A few additional Meson-specific options you will find handy:

-Dstatic_themes=true— compile default themes into the binary so they are available even if not installed on disk.-Dnogpl=true— avoid GPL-only components.-Duse_webui=true— build/install bundled WebUIs.

Examples (Meson):

- Basic configure + build (default options):

meson setup builddir

ninja -C builddir

- Configure with options and a prefix:

meson setup builddir --prefix=/usr -Dlocal=true -Dwant_qjs=false -Duse_capstone_version=v5

ninja -C builddir

ninja -C builddir install

- Single-line example using environment variables and a release build:

CC=clang LDFLAGS='-fuse-ld=gold' meson setup release --buildtype=release --prefix=$HOME/.local -Dlocal=true -Dstatic_runtime=false

ninja -C release

Notes on plugin selection parity between Make and Meson:

- Make uses

configure-pluginsand theplugins.cfgmechanism. - Meson accepts a

-Dpluginsoption and also exposes flags for static/shared linking via-Duse_dylinkand-Dstatic_runtime. The semantics are slightly different but accomplish the same goal: control which plugins are built and how they are linked.

Quick workflow examples

Build with GNU Make, local prefix, and static plugins for smaller distribution:

./configure-plugins --static io.bind asm.mycpu

./configure --prefix=$HOME/.local --disable-debugger --without-qjs

make -j$(nproc)

make install

The Make build system also permits doing installations with symlinks, so you don't have to reinstall after recompiling because all system-wide files will be pointing to the ones in the builddir.

Build with Meson, minimal plugin set, release build:

meson setup release --buildtype=release --prefix=$HOME/.local -Dplugins='io.debug,asm.x86' -Dwant_qjs=false -Duse_sys_capstone=true

ninja -C release

ninja -C release install

Cleaning and housekeeping

To ensure a clean tree before rebuilding:

git clean -xdf

git reset --hard origin/master

git pull

If you need to remove previously installed files when switching prefixes, run the make purge step after configuring with the intended prefix.

Windows Binaries

To build radare2 on Windows, use the Meson build system. While you can compile r2 on Windows with Cygwin, MinGW, or WSL using the acr/make build system, those methods are unofficial and unsupported and may produce unexpected results.

Prebuilt binaries are available on the releases page. If you're signed in to GitHub, you can also access the CI artifacts that are produced for every commit.

Prerequisites

Building radare2 on Windows using Microsoft Visual Studio involves setting up several key tools. You will need to install Microsoft Visual Studio, along with the Meson build system and the Ninja build tool. These tools are necessary for configuring and compiling the radare2 source code.

These are the requirements to get the environment ready.

- 3 GB of free disk space

- Visual Studio (2019 or higher)

- Python 3

- Meson

- Ninja

- Git

Downloading the code

You may need to download the zip/tgz or git clone the last code from git in order to run the following commands in cmd or powershell:

git clone https://github.com/radareorg/radare2

Follow these instructions to pull the build tools to get the project compiled on your Windows machine.

Native Windows Compilation

The build process on windows has been heavily simplified to just 3 batch scripts, which is how it's executed in the CI and the recommended workflow.

The scripts expect you to have Python, Git, Visual Studio and PowerShell, and will run Meson and Ninja by default (both easily installable via pip).

preconfigure.batfind vscode, checks for python installation etcconfigure.batrun the meson configure step.make.batbuild radare2 and createprefixdirectory with the distributable folder.

You can run make from the root directory of the project everytime you modify the source code in case you are developing to get the new binaries ready to test in that directory.

The configure.bat will also create a directory named vs which contains the visual studio project in case you want to use the graphical IDE for developing or debugging. This .vsproj is constructed automatically from the meson scripts, this simplifies maintainance.

Crosscompiling

MinGW builds are supported, but official releases are compiled with the Microsoft compiler to maximize compatibility and standardization with other Windows software.

If you want to build r2 for Windows on Linux, use the sys/mingw32.sh script — it autodetects the MinGW toolchain on your system and produces the .exe and .dll files.

Note: Cygwin support was largely removed several years ago. Today, most users prefer WSL or native builds, which also work well on ReactOS and across many Windows versions without requiring extra compatibility software.

Installing Build Dependencies

Take the following sub-sections of this chapter as a guide to install the software you need to compile radare2 from source:

Install Visual Studio 2019 (or higher)

Please install Visual Studio with the Visual C++ toolset (MSVC), the C++ libraries, and the Windows SDK that matches your target platform.

You can download Visual Studio — the Community editions are free — from here:

Install Python3

Conda is probably the best Python distribution for Windows, but if you already have Python installed you can skip the following steps.

You can install Python3 on Windows using Conda, the official installer, or package managers like choco or winget — pick whichever you prefer.

After installing, make sure the Python bin directory is on your PATH so you can open CMD or PowerShell and run python3 (for example, python3 --version to verify).

Now you are ready to install meson and ninja — the radare2 build tools — using pip:

pip install ninja

pip install meson

Install Git for Windows

All Radare2 code is managed with Git and hosted on GitHub.

To install Git for Windows, follow these steps:

-

Download Git for Windows from the official website.

-

In the installation wizard, choose the following options:

- Use a TrueType font in all console windows

- Use Git from the Windows Command Prompt

- Use the native Windows Secure Channel library (instead of OpenSSL)

- Checkout Windows-style, commit Unix-style line endings (

core.autocrlf=true) - Use Windows' default console window (instead of Mintty)

*. After installation, verify it by running git --version to confirm Git is available.

Compiling for Android

Radare2 can be cross-compiled for other architectures/systems as well, like Android.

Prerequisites

- Python 3

- Make

- Git

- Binutils

- pkg-config

Step-by-step

Download and Install Termux App

Download the Termux application from the official site and install it.

Update & Upgrade

First time installation of termux require updating the repo to fetch all the available packages.

$ pkg update && pkg upgrade -y

Install required packages

$ pkg install build-essential git python3 binutils wget pkg-config

build-essential contains all the required build tool like make,gcc etc.

Download or clone Radare2 repo

$ git clone https://github.com/radareorg/radare2

If you are limited by disk space, you can either clone the repository with a depth of 1 by adding --depth 1 in clone command or build from a tarball. Cloning the repository provides the most up-to-date code, whereas tarballs are only generated during releases, which may not contains latest update and bug fixes.

Build and Installation

Building and installing Radare2 after cloning the repository is straightforward using the following commands:

cd radare2

sh sys/install.sh

It will install required packages if you already didn't and start the installation.

~/radare2 $ sh sys/install.sh

/data/data/com.termux/files/home/radare2

Termux environment detected. Installing necessary packages

No mirror or mirror group selected. You might want to select one by running 'termux-change-repo'

Checking availability of current mirror:

[*] https://packages-cf.termux.dev/apt/termux-main: ok

Hit:1 https://packages-cf.termux.dev/apt/termux-main stable InRelease

Reading package lists... Done

Building dependency tree... Done

Reading state information... Done

All packages are up to date.

No mirror or mirror group selected. You might want to select one by running 'termux-change-repo'

Checking availability of current mirror:

[*] https://packages-cf.termux.dev/apt/termux-main: ok

Reading package lists... Done

Building dependency tree... Done

Reading state information... Done

git is already the newest version (2.45.2).

build-essential is already the newest version (4.1).

binutils is already the newest version (2.42).

pkg-config is already the newest version (0.29.2-2).

0 upgraded, 0 newly installed, 0 to remove and 0 not upgraded.

/data/data/com.termux/files/home/radare2

From https://github.com/radareorg/radare2

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

Already up to date.

[*] Finding make is /data/data/com.termux/files/usr/bin/make OK

[*] Configuring the build system ... OK

[*] Checking out capstone... OK

[*] Checking out vector35-arm64... OK

[*] Checking out vector35-armv7... OK

[*] Running configure... OK

[*] Ready. You can now run 'make'.

configure-plugins: Loading ./plugins.cfg ..

configure-plugins: Generating libr/config.h

configure-plugins: Generating libr/asm/d/config.inc

configure-plugins: Generating libr/config.mk

........

........

cd "/data/data/com.termux/files/usr/lib/radare2/" && rm -f last && ln -fs 5.9.3 last

cd "/data/data/com.termux/files/usr/share/radare2/" && rm -f last && ln -fs 5.9.3 last

mkdir -p "/data/data/com.termux/files/usr/share/radare2/5.9.3/"

/data/data/com.termux/files/usr/bin/sh ./configure-plugins --rm-static //data/data/com.termux/files/usr/lib/radare2/last/

configure-plugins: Loading ./plugins.cfg ..

Removed 0 shared plugins that are already static

~/radare2 $ r2 -v

radare2 5.9.3 275 @ linux-arm-64

birth: git.5.9.2-146-g13ea460 2024-06-28__20:22:10

commit: 13ea460b3ea28ef37361eb1d679561037c521d27

options: gpl -O? cs:5 cl:2 make

Flatpak releases

The easiest way to get iaito and radare2 installed in your Linux distro is by using Flatpak.

This method ensures a well-tested, sandboxed environment that doesn't interfere with your system dependencies. In this section, we will guide you through the steps to install and configure iaito using Flatpak.

First, ensure that Flatpak is installed and configured on your system. If Flatpak is not already installed, you can add it through your distribution's package manager. For example, on Debian-based systems, you can install Flatpak with the following command:

sudo apt install flatpak

Next, you need to add the Flathub repository, which hosts iaito and many other applications. Run the following command to add Flathub:

flatpak remote-add --if-not-exists flathub https://flathub.org/repo/flathub.flatpakrepo

With Flatpak and the Flathub repository set up, you can install iaito by executing the following command in your terminal:

flatpak install flathub org.radare.iaito

During the installation process, you may be prompted to confirm the installation and to enter your user password. Flatpak will handle all necessary dependencies for iaito, ensuring a smooth installation process. Once the installation is complete, you can launch iaito using the following command:

flatpak run org.radare.iaito

CLI Configuration

To allow usage of CLI radare applications you need to define the following aliases:

alias r2='flatpak run --command=r2 org.radare.iaito'

alias r2agent='flatpak run --command=r2agent org.radare.iaito'

alias r2p='flatpak run --command=r2p org.radare.iaito'

alias r2pm='flatpak run --command=r2pm --share=network --devel org.radare.iaito'

alias r2r='flatpak run --command=r2r org.radare.iaito'

alias rabin2='flatpak run --command=rabin2 org.radare.iaito'

alias radare2='flatpak run --command=radare2 org.radare.iaito'

alias radiff2='flatpak run --command=radiff2 org.radare.iaito'

alias rafind2='flatpak run --command=rafind2 org.radare.iaito'

alias ragg2='flatpak run --command=ragg2 org.radare.iaito'

alias rahash2='flatpak run --command=rahash2 org.radare.iaito'

alias rarun2='flatpak run --command=rarun2 org.radare.iaito'

alias rasign2='flatpak run --command=rasign2 org.radare.iaito'

alias rasm2='flatpak run --command=rasm2 org.radare.iaito'

alias ravc2='flatpak run --command=ravc2 org.radare.iaito'

alias rax2='flatpak run --command=rax2 org.radare.iaito'

With this commands, by default no local files will be accesible.

To allow acces to a folder please use the special permissions procedure explained below or use zenity inside the flatpak sandbox to open a dialog using XDG portals.

Example:

$ alias r2='flatpak run --command=r2 org.radare.iaito'

$ r2 -

[0x00000000]> o `!zenity --file-selection`

Sandbox Configuration

To manage the sandbox permissions for iaito, you can use the Flatseal utility. Flatseal allows you to configure Flatpak application permissions easily.

Install Flatseal with the following command:

flatpak install flathub com.github.tchx84.Flatseal

Then, run Flatseal to adjust iaito's permissions:

flatpak run com.github.tchx84.Flatseal

Alternatively this can be configured via CLI using flatpak override, here there are some examples on how to configure it:

- To allow radare plugins to connect to your network or Internet:

flatpak override --user --share=network org.radare.iaito

- To allow some plugins to attach to a usb device:

flatpak override --user --device=all org.radare.iaito

- To allow some plugins to access to an specific folder not selected by the GUI (with optional

:roto only allow read only):

flatpak override --user --filesystem=/mnt/hdd:ro org.radare.iaito

- To reset back to default required permissions this command can be used:

flatpak override --user --reset org.radare.iaito

The Flatpak version of iaito comes bundled with several useful plugins: r2dec, r2ghidra, r2frida, r2yara, and r2ai. These plugins enhance the functionality of radare2, providing additional capabilities for decompilation, integration with Ghidra, dynamic analysis with Frida, and YARA rule matching.

Snap releases

The Snap package system is a cross-platform solution for packaging and distributing software on Linux. Snaps bundle all necessary dependencies, ensuring they work on any Linux distribution. This makes Snap an ideal choice for distributing radare2.

Radare2 is distributed via Snap by building it from the continuous integration (CI) system for each release. This means every new official release is packaged and made available to Snap users automatically. While the builds are automated, they are only done for official releases, not for every git commit. This ensures that Snap users have a stable and tested version of radare2.

Snap packages can run in a sandboxed environment, isolating them from the rest of the system. This enhances security and prevents conflicts with other software. Sandboxed snaps can request permissions for specific resources, but they remain contained within their sandbox, ensuring stability and security.

To use radare2 Snap builds, note that they have different program names to avoid conflicts with other installations. Snap versions of radare2 programs are prefixed with radare2.. For example, to run the stable build, use:

sudo snap install radare2 --classic

radare2.radare2 /bin/ls

radare2.rabin2 -z /bin/sleep

This way, you can maintain a stable version alongside a development version without conflicts.

To allow using radare commands without this prefix, it can be solved by using shell aliases. So as an example could be something like this:

alias r2='radare2.r2'

alias r2agent='radare2.r2agent'

alias r2frida-compile='radare2.r2frida-compile'

alias r2p='radare2.r2p'

alias r2pm='radare2.r2pm'

alias r2r='radare2.r2r'

alias rabin2='radare2.rabin2'

alias radiff2='radare2.radiff2'

alias rafind2='radare2.rafind2'

alias ragg2='radare2.ragg2'

alias rahash2='radare2.rahash2'

alias rarun2='radare2.rarun2'

alias rasign2='radare2.rasign2'

alias rasm2='radare2.rasm2'

alias ravc2='radare2.ravc2'

alias rax2='radare2.rax2'

alias sleighc='radare2.sleighc'

alias yara='radare2.yara'

alias yarac='radare2.yarac'

Iaito Snap

Also iaito, as a radare GUI, can be installed using this packaging system.

To install it is required to run the following command:

sudo snap install iaito --classic

In the same way radare2 snap include a set of commands, iaito snap also include radare2 commands prefixed with iaito. (for example iaito.r2, iaito.rax2,...).

This commands can be used from CLI, and allow to use the same environment as iaito GUI.

But to use radare2 from CLI it is prefered to install and use the main radare2 snap package.

Docker containers

Docker is a software that use OS-level virtualization to deliver software in packages called images and containers when running them. Containers bundle their own software and are isolated from the host system, this prevents conflicts with other installed software.

There are several implamentations to run Docker images but radare2 images only have been tested with docker, podman and nerdctl.

Available images

There are 2 mantained docker images, one for the official releases and one targeted to be build locally from GIT. Both can be used similarly.

Stable version

This docker image can be found in Docker Hub and contain the latest radare2 stable version. This image is based on Ubuntu and the same radare2 snap build. The Dockerfile used to build it can be found in this dedicated repository.

The resulting build includes the following projects:

To use this docker image you can use either:

docker run -ti radare/radare2

podman run -ti docker.io/radare/radare2

nerdctl run -ti radare/radare2

To use the docker image as one shot so it removes everything inside the container on exit just add --rm as follows:

docker run --rm -ti radare/radare2

Another example to use for debugging inside the docker:

docker run --tty --interactive --privileged --cap-add=SYS_PTRACE --security-opt seccomp=unconfined --security-opt apparmor=unconfined radare/radare2

GIT version

Alternatively there is a version from radare2 GIT aimed to be build locally, also called r2docker.

This will build an image using Debian with radare2 from GIT with latest changes.

The Dockerfile to build can be found inside the dist/docker directory in the radare2 source tree.

To build this other image run the following lines:

git clone https://github.com/radareorg/radare2.git

cd radare2

make -C dist/docker

This will build an image with the following plugins by default:

It is possible to specify more packages using the R2PM make variable:

make -C dist/docker R2PM=radius2

Also, you can select the architecture (amd64 / arm64) to compile the image by using the ARCH make variable.

This Dockerfile also used by Remnux distribution from SANS, and is available on the Docker Hub, but it might not contain latest changes.

Run a container as r2web server

By default both images are intended to be used in a interactive terminal.

But both can also be launched directly to use the radare2 web UI.

The do so it can be launched using the following command:

docker run -p 9090:9090 radare/radare2 r2 -c '=h' -

Or the following docker-compose structure:

version: "3.8"

services:

radare2:

image: radare/radare2

command: r2 -c '=h' -

network_mode: bridge

ports:

- "9090:9090"

Or if debugging functionality is required:

version: "3.8"

services:

radare2:

image: radare/radare2

command: r2 -c '=h' -

network_mode: bridge

ports:

- "9090:9090"

privileged: true

cap_add:

- SYS_PTRACE

security_opt:

- "seccomp=unconfined"

- "apparmor=unconfined"

Troubleshooting

Sometimes, old builds or conflicting versions can cause problems, such as tools using the wrong version of libraries, plugins not loading, or crashes with segmentation faults at startup. Here are some steps to help you resolve these issues.

We will assume you have tried to build radare2 with meson and make:

- your builddir doesnt contain spaces

- the repository is a clean clone

- you read the error messages carefully

- you have at least make, gcc, git, patch working

First, if you encounter issues during startup, you can use the R2_DEBUG=1 environment variable to see detailed debugging information. This can help you understand what is going wrong during the initialization of radare2.

export R2_DEBUG=1

radare2 -

To remove old builds of radare2 from your system, you can run the make purge command. This command will remove previous installations of radare2 from various common prefix paths.

./configure --prefix=/old/r2/prefix/installation

make purge

Additionally, you may need to remove the plugin directory from your home directory to ensure no old or incompatible plugins are causing issues. You can do this by deleting the local/share/radare2/plugins directory.

rm -rf ~/.local/share/radare2/plugins

If you use r2pm (radare2 package manager), it is also a good idea to clear the r2pm cache to free up some disk space and remove potentially problematic cached files. You can do this by deleting the ~/.local/share/radare2/r2pm directory.

rm -rf ~/.local/share/radare2/r2pm

By following these steps, you can clean up old installations and resolve common issues that might arise during the installation and usage of radare2.

Using Radare2

The learning curve is usually somewhat steep at the beginning. Although after an hour of using it you should easily understand how most things work, and how to combine the various tools radare offers. You are encouraged to read the rest of this book to understand how some non-trivial things work, and to ultimately improve your skills.

Navigation, inspection and modification of a loaded binary file is performed using three simple actions: seek (to position), print (buffer), and alternate (write, append).

The 'seek' command is abbreviated as s and accepts an expression as its argument. The expression can be something like 10, +0x25, or [0x100+ptr_table]. If you are working with block-based files, you may prefer to set the block size to a required value with b command, and seek forward or backwards with positions aligned to it. Use s++ and s-- commands to navigate this way.

If radare2 opens an executable file, by default it will open the file in Virtual Addressing (VA) mode and the sections will be mapped to their virtual addresses. In VA mode, seeking is based on the virtual address and the starting position is set to the entry point of the executable. Using -n option you can suppress this default behavior and ask radare2 to open the file in non-VA mode for you. In non-VA mode, seeking is based on the offset from the beginning of the file.

The 'print' command is abbreviated as p and has a number of submodes — the second letter specifying a desired print mode. Frequent variants include px to print in hexadecimal, and pd for disassembling.

To be allowed to write files, specify the -w option to radare2 when opening a file. The w command can be used to write strings, hexpairs (x subcommand), or even assembly opcodes (a subcommand). Examples:

> w hello world ; string

> wx 90 90 90 90 ; hexpairs

> wa jmp 0x8048140 ; assemble

> wf inline.bin ; write contents of file

Appending a ? to a command will show its help message, for example, p?.

Appending ?* will show commands starting with the given string, e.g. p?*.

To enter visual mode, press V<enter>. Use q to quit visual mode and return to the prompt.

In visual mode you can use HJKL keys to navigate (left, down, up, and right, respectively). You can use these keys in cursor mode toggled by c key. To select a byte range in cursor mode, hold down SHIFT key, and press navigation keys HJKL to mark your selection.

While in visual mode, you can also overwrite bytes by pressing i. You can press TAB to switch between the hex (middle) and string (right) columns. Pressing q inside the hex panel returns you to visual mode. By pressing p or P you can scroll different visual mode representations. There is a second most important visual mode - curses-like panels interface, accessible with V! command.

Commandline

Radare2 can be used directly from the command line, allowing you to run commands without entering the interactive mode. This is handy for quick tasks or when you want to include radare2 in shell scripts. You can perform analyses, extract information, or manipulate binary files with just a single line in your terminal.

For example, if we want to show 10 bytes from the entrypoint directly from the system shell we can use:

$ r2 -q -c 'p8 10 @ entry0' /bin/ls

The -q flag is by definition the quiet mode, but when combined with -c it will return to the shell right after executing the specified commands.

Command-line flags are options you add when starting radare2. These flags let you customize how radare2 behaves from the start. You can tell radare2 to analyze a file immediately, use a specific configuration, or set various other parameters. Understanding these flags helps you set up radare2 efficiently for different tasks.

We can set some options at startup time with the -e flag like this:

r2 -e scr.color=0 -e io.cache=true /bin/ls

The help message, accessed by running radare2 with the -h flag, shows all available options. It's a quick reference for radare2's capabilities. By exploring this message, you can discover features you might not know about.

$ radare2 -h

Usage: r2 [-ACdfjLMnNqStuvwzX] [-P patch] [-p prj] [-a arch] [-b bits] [-c cmd]

[-s addr] [-B baddr] [-m maddr] [-i script] [-e k=v] file|pid|-|--|=

-- run radare2 without opening any file

- same as 'r2 malloc://512'

= read file from stdin (use -i and -c to run cmds)

-= perform !=! command to run all commands remotely

-0 print \x00 after init and every command

-2 close stderr file descriptor (silent warning messages)

-a [arch] set asm.arch

-A run 'aaa' command to analyze all referenced code

-b [bits] set asm.bits

-B [baddr] set base address for PIE binaries

-c 'cmd..' execute radare command

-C file is host:port (alias for -c+=http://%s/cmd/)

-d debug the executable 'file' or running process 'pid'

-D [backend] enable debug mode (e cfg.debug=true)

-e k=v evaluate config var

-f block size = file size

-F [binplug] force to use that rbin plugin

-h, -hh show help message, -hh for long

-H ([var]) display variable

-i [file] run script file

-I [file] run script file before the file is opened

-j use json for -v, -L and maybe others

-k [OS/kern] set asm.os (linux, macos, w32, netbsd, ...)

-l [lib] load plugin file

-L, -LL list supported IO plugins (-LL list core plugins)

-m [addr] map file at given address (loadaddr)

-M do not demangle symbol names

-n, -nn do not load RBin info (-nn only load bin structures)

-N do not load user settings and scripts

-NN do not load any script or plugin

-q quiet mode (no prompt) and quit after -i

-qq quit after running all -c and -i

-Q quiet mode (no prompt) and quit faster (quickLeak=true)

-p [prj] use project, list if no arg, load if no file

-P [file] apply rapatch file and quit

-r [rarun2] specify rarun2 profile to load (same as -e dbg.profile=X)

-R [rr2rule] specify custom rarun2 directive

-s [addr] initial seek

-S start r2 in sandbox mode

-t load rabin2 info in thread

-u set bin.filter=false to get raw sym/sec/cls names

-v, -V show radare2 version (-V show lib versions)

-w open file in write mode

-x open without exec-flag (asm.emu will not work), See io.exec

-X same as -e bin.usextr=false (useful for dyldcache)

-z, -zz do not load strings or load them even in raw

Common Uses

At first sight it may seem like there are so many options and without some practical use cases it may feel a bit overwhelming, this sections aims to address that by sharing some of the most common ways to get started.

Open a file in write mode and do not parse the headers (raw mode).

$ r2 -nw file

Quickly get into the r2 shell opening a 512B malloc virtual file, handy for testing things. note that a single dash is an alias for malloc://512

$ r2 -

Specify which sub-binary you want to select when opening a fatbin file:

$ r2 -a ppc -b 32 ls.fat

Run a script before entering the prompt:

$ r2 -i patch.r2 target.bin

Execute a command and quit without entering the interactive mode:

$ r2 -qc ij hi.bin > imports.json

Set the configuration variable:

$ r2 -e scr.color=0 blah.bin

Spawn and start debugging a program:

$ r2 -d ls

Attach to an already running process by its process id (PID):

$ r2 -d 1234

Load an existing project file:

$ r2 -p test

Command Syntax

In a single line we can describe the syntax of the radare2 commands like this:

.- ignore special characters, same as full command quotes "?e hi > ho"

| .- interpret the output of the command or run a script `.?`

| / .-- the repeat prefix operator, run a command N times .------------.

| | / . the command to run | , = csv |

| | | / . command suffix output modifier --------------< j = json |

| | | | / | * = r2cmds |

| | | | | `------------'

['][.][N][cmd[,?*j]][~filter][@[@[@]]addr!size][|>pipe] ; another command

| | | | \________/ | | |

| | | | | | \ `--- cmd separator

output filter modifier _.' / | | | \ `-- redirect to file

@ temporal seek --------' / | \ `--- pipe to system shell

@@ foreach operator ---' | `--- foreach modifiers @? @@? @@@?

`--- advanced foreach (addr+size on items)

People who use Vim daily and are familiar with its commands will find themselves at home. You will see this format used throughout the book. Commands are identified by a single case-sensitive character [a-zA-Z].

As an exercise for the reader you may want to read the following lines and understand the purpose of the syntax with examples.

ds ; call the debugger's 'step' command

px 200 @ esp ; show 200 hex bytes at esp

pc > file.c ; dump buffer as a C byte array to file.c

wx 90 @@ sym.* ; write a nop on every symbol

pd 2000 | grep eax ; grep opcodes that use the 'eax' register

px 20 ; pd 3 ; px 40 ; multiple commands in a single line

Repetitions

To repeatedly execute a command, prefix the command with a number:

px # run px

3px # run px 3 times

An useful way to use this command is to draw the classic donut animation with 100?3d or perform an specific amount of steps when debugging like: 10ds (that will do the same as ds 10

Shell Execution

The ! prefix is used to execute a command in shell context. If you want to use the cmd callback from the I/O plugin you must prefix with :.

Note that a single exclamation mark will run the command and print the output through the RCons API. This means that the execution will be blocking and not interactive. Use double exclamation marks -- !! -- to run a standard system call.

All the socket, filesystem and execution APIs can be restricted with the cfg.sandbox configuration variable.

Environment

When executing system commands from radare2, we will get some special environment variables that can be used to script radare2 from shellscripts without the need to depend on r2pipe.

The environment variables can be listed and modified with the % command.

Note that the environment variables will be different depending on how we execute code with radare2:

- runtime environment (R2CORE tells where the instance is in memory)

- debugger environment (as clean as described in a rarun2 profile)

- spawning processes with ! (get some context details, like offset, file, ..)

- r2pipe environment (

R2PIPE_INandR2PIPE_OUTwith the pipe descriptors)

[0x00000000]> !export | grep R2_

export R2_ARCH="arm"

export R2_BITS="64"

export R2_BSIZE="256"

export R2_COLOR="0"

export R2_DEBUG="0"

export R2_ENDIAN="little"

export R2_FILE="malloc://512"

export R2_IOVA="1"

export R2_OFFSET="0"

export R2_SIZE="512"

export R2_UTF8="1"

export R2_XOFFSET="0x00000000"

[0x00000000]>

We can also find the location in memory of the RCore instance in the current process. This can be useful when injecting code inside radare2 (like when injecting r2 via r2frida or using native api calls on live runtimes without having to pass pointers or depend on RLang setups) We may learn more about this in the scripting chapter.

[0x00000000]> %~R2

R2CORE=0x140018000

[0x00000000]>

Pipes

The standard UNIX pipe | is also available in the radare2 shell. You can use it to filter the output of an r2 command with any shell program that reads from stdin, such as grep, less, wc. If you do not want to spawn anything, or you can't, or the target system does not have the basic UNIX tools you need (Windows or embedded users), you can also use the built-in grep (~).

Filtering

The ~ is a special character that is used by the console filtering features. It can be chained multiple times to perform multiple filters like grepping, xml or json indentation, head/tail operations, select column of output, etc

You may find that ~ is very similar to using the unix | pipe, but this

As you may expect appending a question mark will display the help message.

[0x00000000]> ~?

Usage: [command]~[modifier][word,word][endmodifier][[column]][:line]

modifier:

| & all words must match to grep the line

| $[n] sort numerically / alphabetically the Nth column

| $ sort in alphabetic order

| $$ sort + uniq

| $! inverse alphabetical sort

| $!! reverse the lines (like the `tac` tool)

| , token to define another keyword

| + case insensitive grep (grep -i)

| * zoom level

| ^ words must be placed at the beginning of line

| ! negate grep

| ? count number of matching lines

| ?. count number chars

| ?? show this help message

| ?ea convert text into seven segment style ascii art

| :s..e show lines s-e

| .. internal 'less'

| ... internal 'hud' (like V_)

| .... internal 'hud' in one line

| :) parse C-like output from decompiler

| :)) code syntax highlight

| <50 perform zoom to the given text width on the buffer

| <> xml indentation

| {: human friendly indentation (yes, it's a smiley)

| {:.. less the output of {:

| {:... hud the output of {:

| {} json indentation

| {}.. less json indentation

| {}... hud json indentation

| {=} gron-like output (key=value)

| {path} json path grep

endmodifier:

| $ words must be placed at the end of line

column:

| [n] show only column n

| [n-m] show column n to m

| [n-] show all columns starting from column n

| [i,j,k] show the columns i, j and k

Examples:

| i~:0 show first line of 'i' output

| i~:-2 show the second to last line of 'i' output

| i~:0..3 show first three lines of 'i' output

| pd~mov disasm and grep for mov

| pi~[0] show only opcode

| i~0x400$ show lines ending with 0x400

The ~ character enables internal grep-like function used to filter output of any command:

pd 20~call ; disassemble 20 instructions and grep output for 'call'

Additionally, you can grep either for columns or for rows:

pd 20~call:0 ; get first row

pd 20~call:1 ; get second row

pd 20~call[0] ; get first column

pd 20~call[1] ; get second column

Or even combine them:

pd 20~call:0[0] ; grep the first column of the first row matching 'call'

This internal grep function is a key feature for scripting radare2, because it can be used to iterate over a list of offsets or data generated by disassembler, ranges, or any other command. Refer to the loops section (iterators) for more information.

Output Evaluation

The . character at the begining of the command is used to interpret or evaluate the output of the command you execute.

The purpose of this syntax rings some bells when you use the * suffix or the -r flag in all the r2 shell commands.

For example, we can load the symbols from a binary in disk by running the following line:

> .!rabin2 -rs $R2_FILE

Temporal Seek

The @ character is used to specify a temporary offset at which the command to its left will be executed.

The original seek position in a file is then restored.

For example, pd 5 @ 0x100000fce to disassemble 5 instructions at address 0x100000fce.

Most of the commands offer autocompletion support using <TAB> key, for example seek or flags commands.

It offers autocompletion using all possible values, taking flag names in this case.

The command history can be interactively inspected with !~....

To extend the autocompletion support to handle more commands or enable autocompletion to your own commands defined in core, I/O plugins you must use the !!! command.

Expressions

Expressions are mathematical representations of 64-bit numerical values. These are handled anywhere RNum API is used, the api takes a string that can contain multiple math operations with different numeric bases and operations and computes the resulting value.

They can be displayed in different formats, be compared or used with all commands accepting numeric arguments. Expressions can use traditional arithmetic operations, as well as binary and boolean ones.

To evaluate mathematical expressions prepend them with command ?:

[0xb7f9d810]> ?vi 0x8048000

134512640

[0xv7f9d810]> ?vi 0x8048000+34

134512674

[0xb7f9d810]> ?vi 0x8048000+0x34

134512692

[0xb7f9d810]> ? 1+2+3-4*3

hex 0xfffffffffffffffa

octal 01777777777777777777772

unit 17179869184.0G

segment fffff000:0ffa

int64 -6

string "\xfa\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff\xff"

binary 0b1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111010

fvalue: -6.0

float: nanf

double: nan

trits 0t11112220022122120101211020120210210211201

Supported arithmetic operations are:

+ addition

- subtraction

* multiplication

/ division

% modulus

& binary and

| binary or

^ binary xor

>> shift right

<< shift left

For example, using the ?vi command we the the integer (base10) value resulting it from evaluating the given math expression

[0x00000000]> ?vi 1+2+3

6

To use of binary OR should quote the whole command to avoid executing the | pipe:

[0x00000000]> "? 1 | 2"

hex 0x3

octal 03

unit 3

segment 0000:0003

int32 3

string "\x03"

binary 0b00000011

fvalue: 2.0

float: 0.000000f

double: 0.000000

trits 0t10

Note that on modern r2 versions you can use the single quote at the begining of the command to avoid evaluating the rest of the expression:

'? 1 | 2 is the equivalent to "? 1 | 2"

Numbers can be displayed in several formats:

0x033 : hexadecimal can be displayed

3334 : decimal

sym.fo : resolve flag offset

10K : KBytes 10*1024

10M : MBytes 10*1024*1024

You can also use variables and seek positions to build complex expressions.

Use the ?$? command to list all the available commands or read the refcard chapter of this book.

$$ here (the current virtual seek)

$l opcode length

$s file size

$j jump address (e.g. jmp 0x10, jz 0x10 => 0x10)

$f jump fail address (e.g. jz 0x10 => next instruction)

$m opcode memory reference (e.g. mov eax,[0x10] => 0x10)

$b block size

Some more examples:

[0x4A13B8C0]> ? $m + $l

140293837812900 0x7f98b45df4a4 03771426427372244 130658.0G 8b45d000:04a4 140293837812900 10100100 140293837812900.0 -0.000000

Disassembling the very next instruction after the current one

[0x4A13B8C0]> pd 1 @ +$l

0x4A13B8C2 call 0x4a13c000

Basic Debugger Session

To debug a program, start radare with the -d option. Note that you can attach to a running process by specifying its PID, or you can start a new program by specifying its name and parameters:

$ pidof mc

32220

$ r2 -d 32220

$ r2 -d /bin/ls

$ r2 -a arm -b 16 -d gdb://192.168.1.43:9090

...

In the second case, the debugger will fork and load the debugee ls program in memory.

It will pause its execution early in ld.so dynamic linker. As a result, you will not yet see the entrypoint or any shared libraries at this point.

You can override this behavior by setting another name for an entry breakpoint. To do this, add a radare command

e dbg.bep=entry or e dbg.bep=main to your startup script, usually it is ~/.config/radare2/radare2rc.

Another way to continue until a specific address is by using the dcu command. Which means: "debug continue until" taking the address of the place to stop at. For example:

dcu main

Be warned that certain malware or other tricky programs can actually execute code before main() and thus you'll be unable to control them. (Like the program constructor or the tls initializers)

Below is a list of most common commands used with debugger:

> d? ; get help on debugger commands

> ds 3 ; step 3 times

> db 0x8048920 ; setup a breakpoint

> db -0x8048920 ; remove a breakpoint

> dc ; continue process execution

> dcs ; continue until syscall

> dd ; manipulate file descriptors

> dm ; show process maps

> dmp A S rwx ; change permissions of page at A and size S

> dr eax=33 ; set register value. eax = 33

There is another option for debugging in radare, which may be easier: using visual mode.

That way you will neither need to remember many commands nor to keep program state in your mind.

To enter visual debugger mode use Vpp:

[0xb7f0c8c0]> Vpp

The initial view after entering visual mode is a hexdump view of the current target program counter (e.g., EIP for x86).

Pressing p will allow you to cycle through the rest of visual mode views.

You can press p and P to rotate through the most commonly used print modes.

Use F7 or s to step into and F8 or S to step over current instruction.

With the c key you can toggle the cursor mode to mark a byte range selection

(for example, to later overwrite them with nop). You can set breakpoints with F2 key.

In visual mode you can enter regular radare commands by prepending them with :.

For example, to dump a one block of memory contents at ESI:

<Press ':'>

x @ esi

To get help on visual mode, press ?. To scroll the help screen, use arrows. To

exit the help view, press q.

A frequently used command is dr, which is used to read or write values of the target's general purpose registers.

For a more compact register value representation you might use dr= command.

You can also manipulate the hardware and the extended/floating point registers.

Tooling

Radare2 is not just the only tool provided by the radare2 project. The rest of chapters in this book are focused on explaining the use of the radare2 tool, this chapter will focus on explaining all the other companion tools that are shipped inside the radare2 project.

All the functionalities provided by the different APIs and plugins have also different tools to allow to use them from the commandline and integrate them with shellscripts easily.

Thanks to the ortogonal design of the framework it is possible to do all the things that r2 is able from different places:

- These companion tools

- Native library APIs

- The r2 shell

- Using the high level R2Papi

- Scripting with r2pipe/r2js

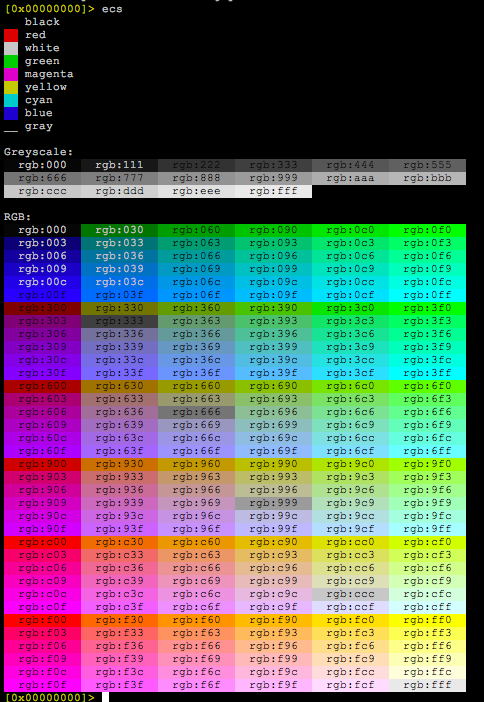

Rax2

The rax2 utility comes with the radare framework and aims to be a minimalistic expression evaluator for the shell. It is useful for making base conversions between floating point values, hexadecimal representations, hexpair strings to ascii, octal to integer. It supports endianness conversion.

This is the help message of rax2, this tool can be used in the command-line or interactively (reading the values from stdin), so it can be used as a multi-base calculator.

Inside r2, the functionality of rax2 is available under the ? command. For example:

[0x00000000]> ? 3+4

As you can see, the numeric expressions can contain mathematical expressions like addition, subtraction, .. as well as group operations with parenthesis.

The syntax in which the numbers are represented define the base, for example:

- 3 : decimal, base 10

- 0xface : hexadecimal, base 16

- 0472 : octal, base 8

- 2M : units, 2 megabytes

- ...

This is the help message of rax2 -h, which will show you a bunch more syntaxes

$ rax2 -h

Usage: rax2 [options] [expr ...]

=[base] ; rax2 =10 0x46 -> output in base 10

int -> hex ; rax2 10

hex -> int ; rax2 0xa

-int -> hex ; rax2 -77

-hex -> int ; rax2 0xffffffb3

int -> bin ; rax2 b30

int -> ternary ; rax2 t42

bin -> int ; rax2 1010d

ternary -> int ; rax2 1010dt

float -> hex ; rax2 3.33f

hex -> float ; rax2 Fx40551ed8

oct -> hex ; rax2 35o

hex -> oct ; rax2 Ox12 (O is a letter)

bin -> hex ; rax2 1100011b

hex -> bin ; rax2 Bx63

ternary -> hex ; rax2 212t

hex -> ternary ; rax2 Tx23

raw -> hex ; rax2 -S < /binfile

hex -> raw ; rax2 -s 414141

-l ; append newline to output (for -E/-D/-r/..

-a show ascii table ; rax2 -a

-b bin -> str ; rax2 -b 01000101 01110110

-B str -> bin ; rax2 -B hello

-d force integer ; rax2 -d 3 -> 3 instead of 0x3

-e swap endianness ; rax2 -e 0x33

-D base64 decode ;

-E base64 encode ;

-f floating point ; rax2 -f 6.3+2.1

-F stdin slurp code hex ; rax2 -F < shellcode.[c/py/js]

-h help ; rax2 -h

-i dump as C byte array ; rax2 -i < bytes

-k keep base ; rax2 -k 33+3 -> 36

-K randomart ; rax2 -K 0x34 1020304050

-L bin -> hex(bignum) ; rax2 -L 111111111 # 0x1ff

-n binary number ; rax2 -n 0x1234 # 34120000

-N binary number ; rax2 -N 0x1234 # \x34\x12\x00\x00

-r r2 style output ; rax2 -r 0x1234

-s hexstr -> raw ; rax2 -s 43 4a 50

-S raw -> hexstr ; rax2 -S < /bin/ls > ls.hex

-t tstamp -> str ; rax2 -t 1234567890

-x hash string ; rax2 -x linux osx

-u units ; rax2 -u 389289238 # 317.0M

-w signed word ; rax2 -w 16 0xffff

-v version ; rax2 -v

Some examples:

Calculator:

$ rax2 3+0x80

0x83

$ rax2 -d "1<<8"

256

Base conversion:

$ rax2 '=2' 73303325

100010111101000010100011101b

The single quote for '=2' is not mandatory for bash but is necessary for some shell like zsh.

Conversion in hex string

$ rax2 -s 4142

AB

$ rax2 -S AB

4142

$ rax2 -S < bin.foo

...

Endianness conversion:

$ rax2 -e 33

0x21000000

$ rax2 -e 0x21000000

33

Base64 decoding

$ rax2 -D ZQBlAA== | rax2 -S

65006500

Randomart:

$ rax2 -K 90203010

+--[0x10302090]---+

|Eo. . |

| . . . . |

| o |

| . |

| S |

| |

| |

| |

| |

+-----------------+

Rafind2

Rafind2 is the command line fronted of the r_search library. Which allows you to search for strings, sequences of bytes with binary masks, etc

$ rafind2 -h

Usage: rafind2 [-mXnzZhqv] [-a align] [-b sz] [-f/t from/to] [-[e|s|S] str] [-x hex] -|file|dir ..

-a [align] only accept aligned hits

-b [size] set block size

-e [regex] search for regex matches (can be used multiple times)

-f [from] start searching from address 'from'

-h show this help

-i identify filetype (r2 -nqcpm file)

-j output in JSON

-m magic search, file-type carver

-M [str] set a binary mask to be applied on keywords

-n do not stop on read errors

-r print using radare commands

-s [str] search for a specific string (can be used multiple times)

-S [str] search for a specific wide string (can be used multiple times). Assumes str is UTF-8.

-t [to] stop search at address 'to'

-q quiet - do not show headings (filenames) above matching contents (default for searching a single file)

-v print version and exit

-x [hex] search for hexpair string (909090) (can be used multiple times)

-X show hexdump of search results

-z search for zero-terminated strings

-Z show string found on each search hit

That's how to use it, first we'll search for "lib" inside the /bin/ls binary.

$ rafind2 -s lib /bin/ls

0x5f9

0x675

0x679

...

$

Note that the output is pretty minimal, and shows the offsets where the string lib is found. We can then use this output to feed other tools.

Counting results:

$ rafind2 -s lib /bin/ls | wc -l

Displaying results with context:

$ export F=/bin/ls

$ for a in `rafind2 -s lib $F` ; do \

r2 -ns $a -qc'x 32' $F ; done

0x000005f9 6c69 622f 6479 6c64 .. lib/dyld........

0x00000675 6c69 622f 6c69 6275 .. lib/libutil.dyli

0x00000679 6c69 6275 7469 6c2e .. libutil.dylib...

0x00000683 6c69 6200 000c 0000 .. lib......8......

0x000006a5 6c69 622f 6c69 626e .. lib/libncurses.5

0x000006a9 6c69 626e 6375 7273 .. libncurses.5.4.d

0x000006ba 6c69 6200 0000 0c00 .. lib.......8.....

0x000006dd 6c69 622f 6c69 6253 .. lib/libSystem.B.